Shakespeare and The Revelation of the Mechanics of the Universe.

Here is the final draft of my final paper. It's not be presented until Friday, but it had to be unloaded today. Some quotes may be missing, but the primary thrust is here. Enjoy my recognition.

Shakespeare and The Revelation of the Mechanics of the Universe

Daniel Lockhart

ENGL 432

Spring 2006

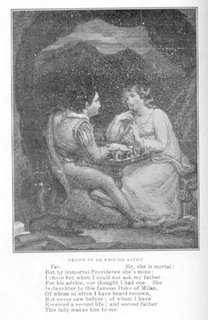

This examination of Shakespeare will pick up where his final play, the Tempest, left us. The knowledge and recognition that I say I’ve gained from this course can easily be summed up in the most memorable scene in this, the greatest of his romance. It is microscopic view of macroscopic structure of the universe. We witness Ferdinand and Miranda playing chess behind a veiled wall, in the most ancient of human dwellings, a cave. This is Shakespeare as Prospero revealing the macrocosmic view of the universe. The chess board, the pieces, the players. These are all the critical elements to function of the universe we as humans have come to inhabit. The old Bard has provided the macrocosmic view to the plain of entities that cannot see outside of their microcosmic view. His series of plays present us with a series of chess boards, the setting if you will. The characters that populate these plays can be seen as the individual pieces.

The chess match is an extremely apt metaphor for the functioning of universe. It is, in essence what Shakespeare has been doing since his first play Henry VI, pt one. In this game, every piece is an archetype, and every setting a board. Each archetype carries with it, its own duties, goals, personalities, and views. There are many different types of boards upon which to play this most ancient game. It is how they are maneuvered that determine the success of each individual piece. The success of each piece is not reliant upon survival, but more upon its ability to fulfill its goal and duty. Each piece, or archetype fails to see the board or setting it inhabits in totality. It is obscured by its microscopic vision of its self and surrounds. The only view each piece has is it’s own interactions with its surroundings and fellow pieces. Characters are these archetypes. People are those characters. What they fail to see is the entities that manipulate the game. Two opposite consciousnesses controlling two opposing sets of pieces or archetypes manipulate the pieces to their own ends.[1] These games occur over limited periods of time, but appear to continue in an unending succession of matches. Gloucester states in King Lear, “As flies are to th’ wanton boys are we to th’ gods: They kill us for their sport.” (King Lear. Act IV, I, 34-45). We are mere pawns in the hands of gods that play with our very existence for sport. Over and over, history shows us that like situations repeat themselves. Similar archetypes arise and fall according to their adherence to cues set forth by these overlying entities.

How is it that Shakespeare is able to understand this and illustrate it to us? The answer to that is simple. Karl Jung was another in the great line of thinkers that brought us a further enhanced view of the macrocosm that we have come to inhabit. Jung and much to the same extent, Emerson[2], and the Transcendalists highlight facts that Shakespeare can merely point to. The understanding of the existence of the great collective consciousness. We are all aspects of this, the great over soul, and only fail to understand the workings of the universe because our senses reduce our understanding to that a microscopic view of the whole. Much of this same sort of viewpoint can be seen in basic Buddhist tenants that claim the soul is confused by our five, inherently flawed senses. Building further upon this, the soul is merely one aspect or part of the larger over-arching entity that is the over soul, or collective consciousness. Certain special individuals are able to pull these all encompassing understandings through themselves and illustrate them to our meager senses. Shakespeare was one of these unique individuals. He was a channeller of the divine. A rare individual that was capable of melding heaven with earth. Like Prospero, he wielded the magic of the island, our island, to illustrate an understanding quite critical to what it was to be human. Shakespeare transformed this knowledge into not only words, but also images, we can form into the basic principles of this understanding.

If we look to the Tempest we can see the crescendo of these images. His previous works are just mere early workings of these images.[3] This play is as blatant an example of this view of the universe as could be produced. Prospero shares so much in common with Will, that we can see him almost as nothing other than Shakespeare. His duty is the director of the action. Coming out of hiding, he is no longer the Duke of Dark Corners we see in Measure for Measure. He is overt, he is magical, and he is in clear command of the actions of the characters on this island. Duke Vincentio is the younger Shakespeare, Prospero the mature Shakespeare. As actor director of this piece we see him direct the end result of this particular group of individuals. He is manipulating the pieces against his opponent. His opponent in this game is time. According to Northrop Frye, so much of this play has to do with time and the concern characters have for it. (Frye pg.178). All along the end results were predetermined, it was merely a matter of hitting his cues on time to complete the end. Still pulling upon basic principles of Buddhism, I would agree with Frye but take this point further. I would argue that all of Shakespeare’s works are enamored with time. They need to be. On stage directions are all reliant upon timing. If Jacques is correct in stating that all the world is a stage, then time becomes more critical then first imagined. Everything within the universe is impermanent. If we all have one duty, a Dharma if you will, during our limited time here then it is critical to understand that timing is everything. This cannot be stressed enough. If we are unable to fulfill our Dharma, the view of our life can be nothing better than the sight of a tragedy. Timing is critical, as in failing to follow our “on stage” cues, we risk missing our chance to complete or tasks. Prospero’s Dharma was to be an apt ruler to his people, and a father to his daughter. By the end of the Tempest he has done this, through his manipulation of magic. Like Hamlet, he procrastinated by his obsession with books. Before the end of this play, he has found his way and assumes his responsibility as a Duke. As such, the tale of Prospero ends as a comedic Romance.

In looking at Richard II we can see the aspects of unfulfilled Dharma and tragedy. Richard’s job in life is to be a king and rule. Like Hamlet, the great procrastinator, he puts off his real job by playing with words. The very poetic nature of Richard II plays into this. According to Bloom this one of Shakespeare’s most lyrical work. Richard becomes so immersed in this that he essentially spells out his own demise. If you look at Prospero in these same terms, his actions mimic those of Richard. The marked difference is that Prospero pulls out of his distraction in time and grasps the cues of our great director at the appropriate moment. Richard misses his endless line of cues to take up the role of king, and continues to focus inward on his own sufferings. “Perhaps we could say that Richard has the language of a major poet but lacks the range, since his only subject is his own sufferings …” (Bloom, pg.253) Poets look outward, or at least good poets look outward and Richard clearly is not capable of doing this. Richard fails to complete his Dharma and as such his time among us must end as failure and hence a tragedy. Prospero fulfills his, as does the Duke in Measure for Measure. As such both of their plays end in a comedic fashion. Time is huge here. Richard does fails to realize neither his procrastination nor Dharma in time. Prospero and the Duke, on other the hand, do. Chess matches, can only last so long. All things are impermanent.

The whole of Shakespeare’s works can be seen in this light. Frye believes that the very essence of tragedy lies in the unfulfilled aspects of comedy. I agree with him, in large part, in regards to this statement. Tragedy occurs as failure to fulfill your Dharma before your limited time is up. Comedy indicates you have fulfilled your duty. The Chess board and pieces supply us with the metaphor for our macrocosmic view of the universe. Two opposing entities, the first of time, the second of Dharma playing for sport with our existence. They compete under these principles in unending sequence from our origins and to time immemorial.[4] By Shakespeare’s connection to the collective consciousness, he has enabled us to see the macrocosmic view of the universe. He has done this through his channeling of individual characters and in turn their reactions to certain settings[5]. Shakespeare has done this with such brilliance that his Dharma of a great revealer, has been obfuscated by our view of him as a playwright. Microscopically we see ourselves as mere pieces in this game. But there is macrocosmic view that is being obscured by confused senses. It was this view that Shakespeare provided us.

Works Cited:

Bloom, Harold . Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human. New York: Riverhead Books, 1998.

Frye, Northrop . Northrop Frye On Shakespeare. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1986.

[1] These consciousness manipulate the events by installing cues and manoeurving other characters around them.

[2] See Ralph Emerson’s essays on the Over-soul and the Poet for insight into this.

[3] Duke Vincentio (Measure for Measure) and Rosalind (As You Like It) are mere early workings of Prospero.

[4] Hence the game of chess in the cave. These are our origins as pawns in the game. We have been manipulated by these same gods since the moment we began to remember. The cave can also be taken as vessel akin to a womb. From this, it is the view that from conception we are pawns in this game.

[5] Settings in this case refers to all encompassing view of their environment. This includes actions done by others.